Paul Linden, PhD

PaulLinden@aol.com • www.being-in-movement.com

Love without power is ineffective.

Power without love is brutality.

Conflict is commonly approached as mental, emotional, spiritual, political, cultural and historical in nature. However, the body’s responses are crucial and are often ignored. Self-regulation on the body level must be a part of the peace process.

The five exercises detailed below are based on my 49 years of practice of Aikido (a nonviolent Japanese martial art) and body awareness work. The five are the simplest, easiest and most broadly useful exercises I have developed (my books and videos describe many more). The exercises are concrete, specific, and reliable. They are not philosophy. They are physiology.

They are simple enough that people can learn them easily and even teach them to others right away. Applying the exercises in conflict resolution and peacemaking is simple enough that people can use them effectively right away.

MOVEMENT RIDDLES

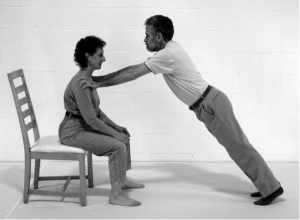

As a preparation for the five exercises, I use the following movement riddles to grab people’s attention and get across some key concepts. I have a student stand in a strong forward-stride stance, and I explain that I want him to resist me when I push on his shoulders. I ask whether the person has any physical or psychological issues which would make that unsafe. I ask him to lean into me a bit and make it very hard for me to move him. The demonstration is much more startling when I work with somebody much bigger and stronger than I. Then I ask the client to raise his eyebrows, and immediately I can easily push him toward his rear. Why? The answer is very simple. Raising the eyebrows is part of the fear/startle reflex, and another part is leaning back to get away from the object of fear. When one part of the startle response is done in the body, the rest of the response fires off too – even though there’s nothing to be afraid of.

following movement riddles to grab people’s attention and get across some key concepts. I have a student stand in a strong forward-stride stance, and I explain that I want him to resist me when I push on his shoulders. I ask whether the person has any physical or psychological issues which would make that unsafe. I ask him to lean into me a bit and make it very hard for me to move him. The demonstration is much more startling when I work with somebody much bigger and stronger than I. Then I ask the client to raise his eyebrows, and immediately I can easily push him toward his rear. Why? The answer is very simple. Raising the eyebrows is part of the fear/startle reflex, and another part is leaning back to get away from the object of fear. When one part of the startle response is done in the body, the rest of the response fires off too – even though there’s nothing to be afraid of.

Another riddle: The student stands in the same stance as before, resisting my push on his shoulders. This time I have the person say something friendly to me and note what happens in his body. Usually there is no effect. Then I have him say something unfriendly and insulting. Almost always the immediate effect of saying something negative is that I can push him back fairly easily. Why? The body responds to unfriendliness and unkindness by contracting, and that interferes with fluid use of the body to achieve effective balance and movement.

A third riddle: Many people use anger as a source of power. Push on the student’s shoulders as in the second riddle. But this time have the student think of something that makes him angry. See whether that creates more stability and strength or less. Most people will experience less balance and less strength when they are angry as compared to when they are calm and kind.

A fourth riddle: Stand in front of a student and grasp his wrist. Now pull him toward you. The student’s task is to not be pulled toward you. Most people brace their posture and resist the pull. That is, of course, one strategy for succeeding at doing what was asked for. However, that strategy, though effective, takes a lot of hard work. I suggest that they simply walk forward. People realize that they understood the instruction to mean “Don’t move forward.” However , the instruction actually was to not be PULLED forward, and the easiest way to do this is to walk forward—and take over the movement. This riddle is about taking a different perspective and how that opens up new options for dealing with difficult situations.

I have found a number of somatic riddles, and they all hinge on taking a different perspective in some fashion. The point is that the body is where peace can be observed and practiced in a clear and concrete way, if you have the tools. These three riddles point to the fact mind and body are the same thing. And they also point to the fact that the optimal way of functioning is based on the integration of power and love.

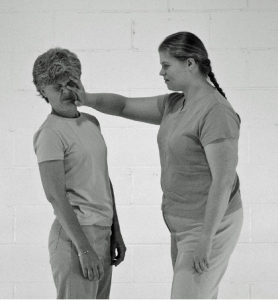

DISTRESS RESPONSE

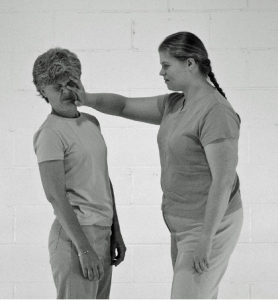

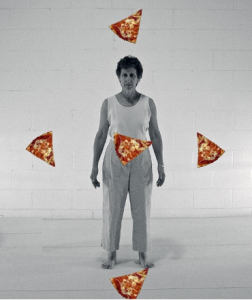

Emotions are physical actions in the body. Feelings are what those actions “taste” like to the person who is doing them.When we are threatened or challenged or hurt, we contract or collapse our posture, breathing, and attention— as the picture of the woman being touched shows. That is the distress response, and it is usually experienced as feelings such as fear, anger, helplessness or numbness.

These powerful physical responses hijack the rational mind and compassionate heart and move our thinking and acting toward oppositional and violent ways of dealing with the challenges we face. Being hurt or hurting someone often leads to dehumanization of the other person and of oneself too, and out of this comes more prejudice and more distress.

When the distress response gets locked into the body, that is the trauma state. You should be aware that in any group of 25 people or so, there are likely to be 1 or 2 survivors of child abuse or other trauma, and body awareness exercises sometimes can throw people into painful emotional states that they had been suppressing. These five peacemaking exercises are also effective for empowerment in trauma recovery work. However, working with trauma is more delicate and requires broader skills and understanding. If someone drops into trauma recall as you teach embodied peacemaking, keep breathing and stay relaxed and steady, and you will find a way to steady the person. Then refer them to a qualified professional.

FIVE EXERCISES

Just as you cannot dig a hole in the water, you cannot stop doing a particular behavior. Instead, you have to start doing an incompatible and more useful behavior. The opposite of and antidote to the physical state of smallness is a state of centered expansiveness. This state of calm alertness and compassionate power moves our thinking and acting toward empathic, assertive and peaceful ways of handling conflicts. And living in the present with compassionate power breaks the chains that bind people to their past trauma.

RELAXED CORE: Let your tongue hang softly in your mouth. Most people will feel that this relaxes the muscles around the neck and shoulders.

Let your shoulders and your armpits hang loose and notice the effect on the rest of your body. Let your belly plop loose. Let your legs hang on the ground. When you breathe, where is the movement in your body? Up into your chest perhaps? That is fear/startle breathing. As you inhale, let your belly expand. Your chest should also expand as you inhale, and the focus of the breathing movement will be on relaxing/expanding the belly. Most people find this very calming.

SMILING HEART: Everyone has something or someone that makes them happy inside —perhaps a friend, a child, a flower, a piece of music. Stand with your eyes closed, and spend a moment thinking about whatever it is that makes you smile inside. What hap-

pens in your body? Most people experience a softening and warmth in their chest, and a freeing up in their entire body.

Can you use your image while you are in a conflict to keep your body stabilized in the feeling of compassion? That would alter your relationship to your opponent. Can you stay anchored in this feeling even when thinking about difficulties in your life?

SHINING: Imagine that you are a star or a firefly or a light bulb. What do you do? You shine. Feel every inch (or centimeter) of your skin glowing outward, as you shine in every direction—as far out as you wish. How does that feel? Most people experience this as spacious and calm.

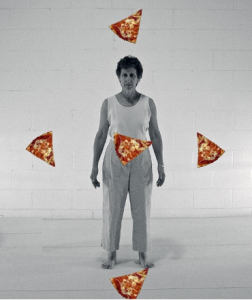

Some people find it easier to imagine something tangible to reach their awareness toward. A popular image is that of reaching toward  slices of pizza.

slices of pizza.

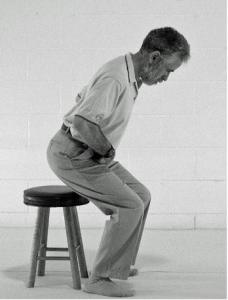

POWER SITTING: Power is necessary to allow

POWER SITTING: Power is necessary to allow

us to function in a loving and peaceful manner. Love without power is weak and ineffective. And of course power without love is brutal and destructive. The development of power starts with postural stability.

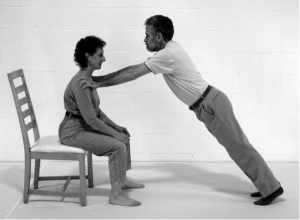

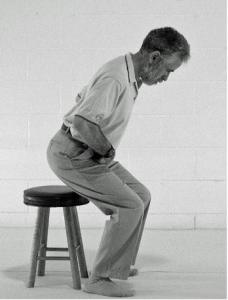

Stand in front of a chair, and get ready to sit down – but in a new way. With each hand, touch your hip joints. Not the hip bones – which are the top edge of the pelvis, but the hip joints – which are in the fold where the legs bend. Imagining a line from the hip joints to the tailbone, push your tailbone back and down along that line. This will lean your torso forward, but not too much. It will take you down to a sitting position. This way of sitting down creates a posture that is very strong yet without effort (see the photo). Most people feel calm, alert, and dignified in this posture.

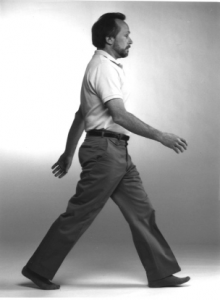

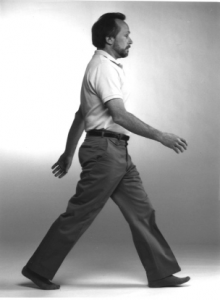

POWER WALKING: There is a standing equivalent of the sitting posture. Walk around barefoot, pay attention to how your legs and feet make your body move forward across the floor. Many people swing a leg forward, and the weight of the leg drags their body forward. Some people put a foot on the floor out in front of them and then pull themselves forward with it. Some people feel that when their foot is behind them, they push themselves forward with it. Stand with your feet together, and jump up in the air. To jump up, you push down. To walk forward most efficiently, you push to the rear with the back leg. A simple way to experience this is to have a partner grasp your belt from behind you. Your partner should pull back and offer moderate resistance to your walking. You will experience that the only way to move forward is to push backwards with the rear leg. People generally experience that when they walk with this awareness of the down/back thrust of the feet, their walk becomes more erect, clearer and more energetic. It is mechanically more efficient and powerful, and it is also much more psychologically confident and alert.

APPLICATIONS

How would you use this body awareness process in managing a conflict? Identifying the emotions as body actions, you could ask, “Where in my body am I doing something? And what am I doing there?” And once you identify what and where the emotions are, you can manage them and break their hold on you. It will not itself be the solution to the conflict, but it will enable you to think and act more freely and come up with a solution if one is possible.

Body-based self-regulation (Embodied Peacemaking) enables people to control their fear and anger and act in peaceful, healthy ways. Deliberately widening and opening yourself in the midst of conflict allows a cooperative peace process to begin unfolding. If you stay centered, you will not see the other person as an enemy or feel the urge to hurt him/her. Deliberately opening when you want to contract or collapse weakens the physical habits within you and lets you live in a centered strong civilized place. Even though this process often works for people right away, regular practice of somatic centering will make it easier to stay centered when a conflict arises.

If the conflict involves a physical attack, though it is counterintuitive, being kind and generous will free your body so that you can fight more effectively – if fighting is the only choice. In the usual verbal disputes, body-based self-regulation enables people to stay focused on the substance of the dispute and not get distracted by the emotions that are stirred up by the dispute. Beyond that, if you notice that your emotions are hijacking the dispute and preventing calm, respectful dialoging, you could ask for a 5-minute body awareness and breathing break.

THROWING TISSUES: A PRACTICE ATTACK

How can we get a practical handle on what conflict is and what its physical effects are? What we need to begin the investigation is a small piece of violence. If it is safe and small-scale, it will not cause unbearable stress, and it will be safe enough to

study. But it must be real enough to arouse a response in you, or it will be not be worth studying.

Ask your partner to stand about six or eight feet away (about two meters) from you and throw balled up tissues at you. Most people find that this mostly symbolic gesture does arouse some fear, but since the “attack” is minimal, so is the fear.

Calibration is important. The exercise must be matched to the student. In working with people who don’t feel much, it is often necessary to increase the stimulus intensity so that they get a response large enough for them to notice. I might wet the tissue so it hits with a soggy and palpable thud. Or I might throw pillows instead of tissues.

On the other hand, I often have people tell me that even throwing a tissue at them feels too intrusive and violent. In that case, standing back farther so that the tissue doesn’t reach them, makes the “attack” even more minimal. Or it may be necessary to do just the movement of throwing the tissue without a tissue at all. Perhaps turning around and throwing the tissue in the wrong direction will help. Or just talking about throwing a tissue, but not moving to do so at all.

The point is to adjust the intensity of the “violence” in this exercise so that it is tolerable and safe for you to examine. For most people that means revising the attack downward in intensity.

Once you have chosen your preferred attack, have your partner attack you and notice what happens in response to the attack. What do you feel? What do you do? What do you want to do?

There are a number of common reactions to the attack with the tissue. People being hit often experience surprise or fear. They may feel invaded and invalidated. Frequently they tense themselves to resist the strike and the feelings it produces. Some people giggle uncontrollably or treat the attack as a game. Many people get angry and wish to hit back. People may freeze in panic, and some people go into a state of shock or dissociation.

Most people talk about feelings and mental states. They are surprised, angry, afraid and so on. They want to escape or fight back. However, a very different way of paying attention to yourself is possible. Notice the details of your muscle tone, breathing, body alignment, and the rhythms and qualities of movement. Where in your body do you feel significant changes? What are you feeling in those locations? Rather than speaking in mental terms— about feelings, thoughts and emotions—it can be very productive to speak in body- based language.

By paying attention to the physical details of your responses, you will begin to see more deeply into the ways you handle conflict. And learning to notice what you do is the first step in changing and improving what you do. Notice what you do in your throat, belly and pelvis. What happens in your chest and back? Notice what you do in your face and head. Notice what you do with your arms/hands and legs/feet. What happens to your breathing? Is there anything else to pay attention to?

Most people realize that they tighten up when they are attacked. They may clench their shoulders or harden their chests. They most likely tense or stop their breathing. They may lean back or lean forward, but it is a tense movement. Sometimes this tension is fear, and people shrink away from the attack. Sometimes this tension is anger, and people lean forward and wish to hit back. Do you do any of these things? Do you also do something else? Many people find that they get limp as a response to being hit. Their breathing

and muscles sag; or they look away and space out, simply waiting for the hitting to be over. They may feel their awareness shrink down to a point or slide away into the distance. Many people find that they experience both rigidity and limpness simultaneously in different areas of the body.

Some people find the role of the attacker far more difficult than the role of the victim, but we will focus on the responses of the person being attacked. However, one idea might make the attacker role easier for you. It will help to remember that your attack is a gift to your partner. By being concerned and benevolent enough to attack your partner, you are allowing them the opportunity to develop self-awareness skills. Without your gracious cooperation, they would not be able to learn these skills, and when they faced real challenges in their lives they would be completely unprepared.

The common denominator in responses of tensing or getting limp is the process of getting smaller. Fear and anger narrow us physically, mentally, emotionally, and spiritually. However, softening and opening the body is the antidote to contraction or collapse.

FURTHER PRACTICE

How can you go further in learning and using Embodied Peacemaking? Daily practice of the for exercises described here will take you a long way.

You could also work through the exercises in one or another of my books or videos, which are available on my website. You could form a study group to have partners to practice with. Unfortunately life brings many conflicts and many traumas, so

there will be no shortage of opportunities for practice.

PAUL LINDEN, Ph.D. is a somatic educator, a martial artist, and an author. He is the developer of Being In Movement® mindbody education. He has a B.A. in Philosophy and a Ph.D. in Physical Education, and is an authorized instructor of the Feldenkrais Method® of somatic education. He has been practicing and teaching Aikido since 1969 and holds a sixth degree black belt in Aikido as well as a first degree black belt in Karate. His work involves the application of body and movement awareness education to such topics as stress management, conflict resolution, computer ergonomics, music or sports performance, and trauma recovery.

Some of Paul Linden’s books and videos

Embodied Peacemaking —Five Easy Exercises. 8 page handout. Free download.

Reach Out: Body Awareness Training for Peacemaking—Five Easy Lessons. 46 pages.

Free download.

Embodied Peacemaking: Body Awareness, Self-Regulation and Conflict Resolution. 164

pages.

Teaching Children Embodied Peacemaking: Body Awareness, Self-Regulation & Conflict

Resolution. 70 pages

Feeling Aikido: Body Awareness Training as a Foundation for Aikido Practice. 300 pages.

Winning is Healing: Body Awareness and Empowerment for Abuse Survivors. 410 pages.

Embodying Power and Love: Body Awareness & Self-Regulation. 10 hour video

Talking with the Body: Body Awareness Methods for Professionals. 9 hour video

Downloadable from www.being-in-movement.com

following movement riddles to grab people’s attention and get across some key concepts. I have a student stand in a strong forward-stride stance, and I explain that I want him to resist me when I push on his shoulders. I ask whether the person has any physical or psychological issues which would make that unsafe. I ask him to lean into me a bit and make it very hard for me to move him. The demonstration is much more startling when I work with somebody much bigger and stronger than I. Then I ask the client to raise his eyebrows, and immediately I can easily push him toward his rear. Why? The answer is very simple. Raising the eyebrows is part of the fear/startle reflex, and another part is leaning back to get away from the object of fear. When one part of the startle response is done in the body, the rest of the response fires off too – even though there’s nothing to be afraid of.

following movement riddles to grab people’s attention and get across some key concepts. I have a student stand in a strong forward-stride stance, and I explain that I want him to resist me when I push on his shoulders. I ask whether the person has any physical or psychological issues which would make that unsafe. I ask him to lean into me a bit and make it very hard for me to move him. The demonstration is much more startling when I work with somebody much bigger and stronger than I. Then I ask the client to raise his eyebrows, and immediately I can easily push him toward his rear. Why? The answer is very simple. Raising the eyebrows is part of the fear/startle reflex, and another part is leaning back to get away from the object of fear. When one part of the startle response is done in the body, the rest of the response fires off too – even though there’s nothing to be afraid of.

slices of pizza.

slices of pizza. POWER SITTING: Power is necessary to allow

POWER SITTING: Power is necessary to allow